Could Hong Kong’s hardy corals be key to saving the world’s threatened reefs?

Corals that can survive Hong Kong’s ‘apocalyptic environment’ offer insight into how to better protect reefs elsewhere

Successful conservation projects have the potential to transform the seas of southern China and beyond

By Stuart Heaver, South China Morning Post

In the chilly waters of Hoi Ha Wan Marine Park, in Sai Kung West Country Park, can be found a conservation success story that has the potential to transform the seas of southern China.

“Hong Kong is the apocalyptic environment for corals,” says Yu-De Pei, a coral researcher from Taiwan who works with Vriko Yu Pik-fan on a pioneering project run by the University of Hong Kong’s Swire Institute of Marine Science (Swims). Yet, Hong Kong still has corals; against all the odds, they have survived a perennial assault by what the two scientists call “stressors”: eutrophication, high turbidity, sedimentation, ocean warming, reclamation, overfishing, plastic pollution, human sewage and drastic sea temperature changes.

In the murky Hoi Ha waters, Yu and Pei demonstrate that, with some help, these hardy corals can not only survive but flourish.

Underwater visibility in the northwestern part of the marine park is about as good as it gets in Hong Kong waters, but on the day we dive, it is restricted to between three and five metres. Only by closely pursuing the white fins of Yu across the coral- strewn seabed is it possible to locate the epicentre of the project.

Appearing through the gloom is a simple PVC piping frame covered with ugly orange industrial webbing. On the structure are about 20 small healthy corals growing in what the two scientists refer to as a nursery.

For about two years, marine ecologists from Swims have been using this nursery as part of a government-sponsored project to help restore coral colonies that fell victim to an ecological catastrophe over the winter months of 2015 and 2016. Nobody is quite sure what caused this “mortality event”, when about 30 per cent of one of the park’s dominant coral species, Platygyra (a form of brain coral common in Hong Kong waters), was killed off or suffered living tissue damage. It could have been a red tide toxic algae bloom, a sudden increase in pollution levels or an extreme temperature change.

“I have been diving for 10 years and I had never seen anything like it,” says Connie Lau Pui-ling, a coral expert and marine parks officer at the Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department (AFCD). “It was alarming.”

After consulting local experts, the AFCD issued an open tender for a scientific partner to come up with a restoration plan for what is probably Hong Kong’s foremost coral location. Swims won the contract and devised a unique rehabilitation scheme for Hoi Ha’s stressed coral.

The plan involves chipping away some of the remaining healthy coral tissue from the skeleton or base and placing it in the underwater nursery, where those fragments can recover their health. The nursery is raised above the seabed so bioeroders (creatures such as sea urchins that feed on coral) can’t get to it and where choking sedimentation is less dense. After the rescued fragments have convalesced for about a year, they are glued with an epoxy resin designed for underwater use onto stable skeletons, or boulders, in the same area. The technique is surprisingly simple though the science behind it is highly complex. And the results are encouraging.

“After one year we can see coral growth and fusion between coral fragments,” says Yu, who reports better than 80 per cent survival rates.

A white guideline leads from the nursery along the seabed, threading its way between outcrops of brain and staghorn coral and shoals of tiny yellow and electric blue damselfish. It leads to newly formed coral communities, each one identified by a number on a blue metal disc.

Yu says they have successfully initiated 30 colonies, some covering large boulders, others measuring between 20cm and 30cm in length.

The Platygyra revival has been so successful that the AFCD has agreed to extend the project to include another species. Now a form of staghorn coral once prevalent in the park is also being nursed in Hoi Ha Wan: Acropora is being grown on concrete tiles on the seabed.

“When we introduced the Acropora a year ago, they were thin sticks like my little finger but now they are small bushes, more like this,” says Yu, clenching her right hand into a fist.

The technique used with this variety is slightly different, with the fragments gathered from Hong Kong waters being initially reared in a laboratory-based nursery before being transplanted to Hoi Ha.

Yu and Pei monitor coral health and growth rates regularly. A water-quality sensor installed nearby can detect algae blooms and red tides, and measure temperature and acidity, so if the coral perishes, at least the scientists stand a good chance of working out why.

“There’s no point reintroducing corals to polluted water just so they can die,” says Yu, who explains why coral restoration is considered controversial. Some within the marine scientific community condemn it as futile because ocean warming is the biggest threat to corals and they believe every research dollar should be invested in reversing the impact of climate change.

“My own view is, what can be the downside of having too much coral?” Yu counters.

She explains how understanding the sex life of Hong Kong corals is essential to achieving successful restoration – and she is not the only local “coral voyeur”.

“Yes, I am interested in the sex life of corals. I love the babies, they are the cutest,” says Apple Chui Pui-yi, a marine biologist and conservationist at the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK), as she peers into one of the shallow tanks of her own laboratory-based coral nursery.

Her “babies” are more properly known as “sexual recruits”. These are juvenile corals cultured in the laboratory from coral larvae captured in the Tolo Harbour.

Corals are hermaphrodites and local varieties, like many others, spawn only once a year. Despite comprehensive research, no one can be sure exactly when spawning will occur but it is always at night, and usually during a full moon in the summer. CUHK divers wait patiently underwater, sometimes for hours at a time over several nights, until thousands of egg-sperm bundles are released into the water column. It is so sensitive a process that the scientists never touch the coral and even switch off their torches during the event, for fear of disturbing it.

“It’s amazing,” says Chui. “The first time I witnessed it, I cried underwater.”

Chui and her colleagues capture larvae in a net and, back at the laboratory, culture, in a good year, about 100 baby corals, the so-called sexual recruits, some of which now sit in tanks of water extracted from Tolo Harbour.

Once abundant, corals in the Tolo Channel were decimated in the 1980s by pollution and sedimentation caused by urbanisation and development around Sha Tin. A near-complete demise was recorded in 1998 and described in scientific circles as “Hong Kong’s first marine ecological disaster”.

Yet even in busy Tolo Harbour, following significant improvements in seawater quality, super-tough Hong Kong corals are making a comeback – albeit with a helping hand.

“Because of many factors, some of the corals just can’t recover naturally so we have to help them out,” says CUHK professor Ang Put, who has spent four years perfecting a restoration technique specifically for Tolo Harbour.

This is why Ang and Chui have a nursery full of recruits: Platygyra, Acropora, Porites (boulder coral) and Goniopora. Alongside Chui’s “babies” are “asexual recruits”: coral fragments that were found on the seabed, having been broken off from their community by storms or, more likely, fishing nets.

Once they have regained their strength, the fragments are reintroduced to Tolo Harbour in much the same way as they are in Hoi Ha.

It is a time-consuming, labour-intensive process but Ang believes it is worthwhile, because the value of a coral community extends beyond the benefits of biodiversity, fish and invertebrate nurseries and attractive sites for divers and snorkellers.Most corals located in tropical regions exist near the upper limit of their survivable temperature range, says Ang, and are vulnerable to extinction from ocean warming. Some 30 per cent of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef was lost in 2016 and a further 20 per cent a year later, bleached by unprecedented ocean warming. In Hong Kong, however, corals have adapted to large temperature ranges (14 to 30 degrees Celsius in some years) and the impact of mass urban development and the consequent “stressors”. How exactly these “survivors” have managed to cling on is the subject of much investigation – and the cause of great hope.

By protecting Hong Kong corals, we are also protecting 10 per cent of the world’s hard-coral gene pool. This could be a genetic resource for the planet – Ang Put, professor, Chinese University of Hong Kong

There are 84 species of hard coral in Hong Kong waters, representing about 10 per cent of those found globally. “By protecting Hong Kong corals, we are also protecting 10 per cent of the world’s hard-coral gene pool,” says Ang. “This could be a genetic resource for the planet.”

Could Hong Kong be key to saving the coral reefs of the world?

“Don’t look down on Hong Kong corals,” says the professor, although he admits that restoration in the city’s waters is still carried out on a minute scale and remains the exclusive preserve of experts.

Chui is trying to change that. She has initiated a public outreach programme called Coral Academy, supported by the AFCD and aimed at secondary schools, and she hopes to recruit volunteer divers as part of the next phase of restoration. She explains that regular monitoring of the restored corals is extremely time consuming and that citizen diver-scientists could perform the task so that restoration might be expanded. She admits, though, that the necessary funding is still being sought and she would prefer the gradual introduction of non-specialists.

Such caution has long since been thrown to the wind along Shenzhen’s Dapeng Peninsula, on the other side of Mirs Bay from Hong Kong.

“We now have nearly 2,400 registered volunteers,” says Morgan Xia Jiaxiang, general secretary of the Shenzhen Dapeng Coral Conservation Volunteer Federation, which was established in 2012 and is more commonly known as Dive4Love. Speaking via WeChat, Xia says his volunteers have placed 35 coral nurseries on the seabed, planted 5,606 corals, rescued 131 coral remnants that were detached by fishing nets and typhoons, and salvaged 1,100kg of seabed waste, including more than 1,800 metres of fishing nets.

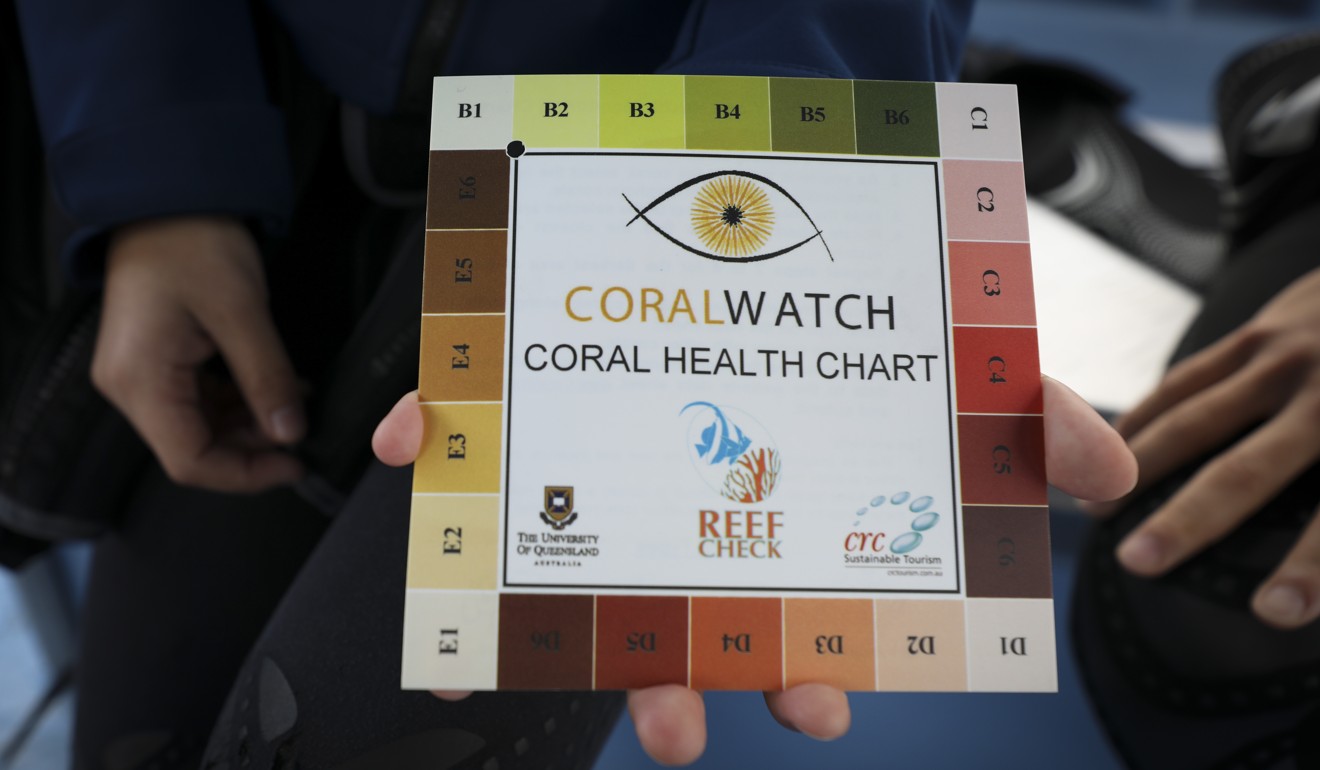

And it appears there would be no shortage of enthusiasm on this side of Mirs Bay should the Coral Academy begin recruiting. The annual Reef Check programme, coordinated by the AFCD since 2000, provides a template for coral monitoring on a voluntary basis. Last year, 79 Reef Check teams, comprising more than 800 volunteer divers, monitored 33 coral sites.

Then there are people such as Harry Chan Tin-ming, an experienced sports diver who leads an informal group of about 50 out on ghost-net and coral clean-ups perhaps twice a month. Ghost nets are abandoned fishing nets that become entangled on rocks and coral communities, damaging coral tissue and trapping fish and invertebrates.

“We are all volunteers and we use our own time, our own kit and our own money,” says Chan.

Chan has removed about 80 to 100 tonnes of ghost nets and associated debris from Hong Kong waters over the past two or three years, he estimates, and says he would very much like to be involved in coral restoration.

“I just need the information from the university, the know-how, and then we need experienced divers,” he says. “We need the younger generation involved, too.”

People like Adam Wang, a Year 12 student at Chinese International School who started keeping a tropical aquarium when he became fascinated with fish and corals as a child. He became a “reefer”, someone who tends corals in tanks at home, and was inspired to learn to dive and establish a school group undertaking beach clean-ups. After impressing Dr David Baker, an associate professor at Swims, with his knowledge of and enthusiasm for coral, he was offered an informal internship at HKU.

“I would love to lead a restoration project but I do have school, too,” says Wang, who has become a regular dive partner of 66-year-old Chan.

There is a growing scientific consensus that due to improvements in sea water quality, coral restoration in Hong Kong waters is becoming ever-more feasible. And there is government support, through the AFCD, and no lack of enthusiasm from the sport-diving community to offer their services as citizen scientists. All of which means there is potential for a large-scale effort to restore Hong Kong’s corals to their former glory and perhaps even help protect the reefs of the world by providing a gene pool of super-tough corals.

“I have been approached by passionate diver groups who want to do coral restoration and, as an ocean lover, I am inclined to be positive,” says the AFCD’s Lau. “But I also need to ask about access to expert ecologists and a properly monitored programme.

“But if the project is well-planned and well-monitored, sure, let’s do it.”

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.