Visionary Study to Protect the High Seas by 2030

The climate action group Greenpeace released a report Thursday which lays out a plan for how world leaders can protect more than 30 percent of the world’s oceans in the next decade—as world governments meet at United Nations to create a historic Global Oceans Treaty aimed at strictly regulating activities which have damaged marine life.

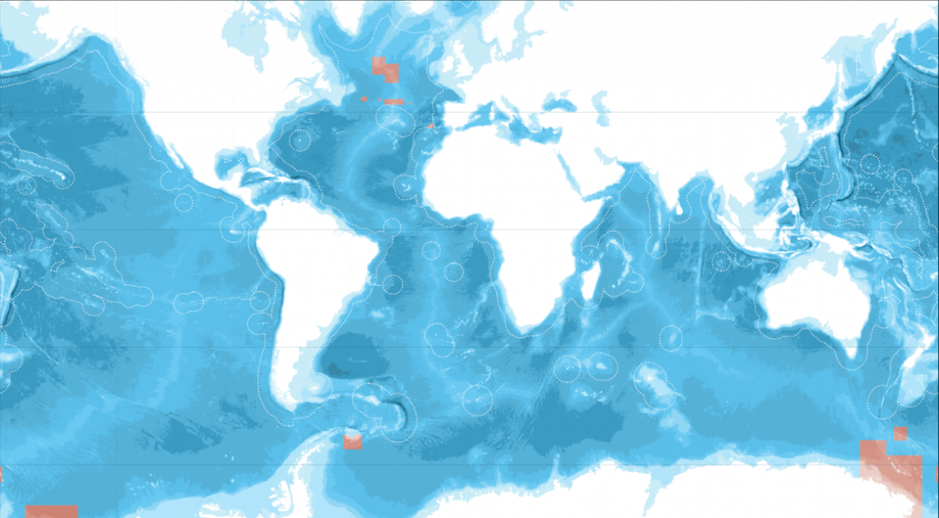

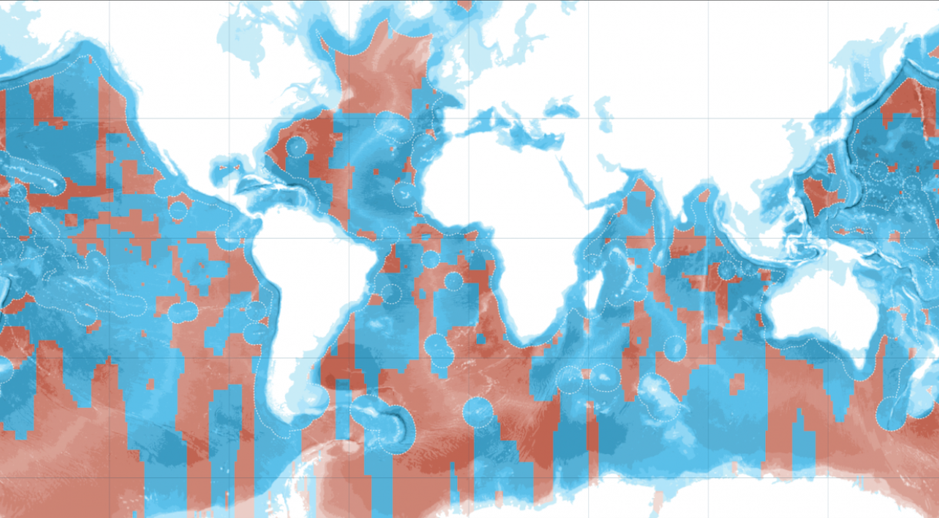

In the report—titled “30×30: A Blueprint for Ocean Protection” (pdf)—researchers from the Universities of York and Oxford divided the world’s oceans into 25,000 62-square mile sections, mapping out a network of “ocean sanctuaries” which could be created to help recover lost biodiversity.

“The findings in this report show that it is entirely feasible to design an ecologically representative, planet-wide network of high seas protected areas to address the crisis facing our oceans and enable their recovery,” reads the report. “The need is immediate and the means readily available. All that is required is the political will.”

“The speed at which the high seas have been depleted of some of their most spectacular and iconic wildlife has taken the world by surprise.” — Callum Roberts,

“The ’30×30′ report puts forward a credible design for a global network of marine protected areas in the high seas based on knowledge accumulated over years by marine ecologists on the distribution of species, including those threatened with extinction, habitats known to be hotspots of biodiversity and unique ecosystems,” said Alex Rogers, a professor at Oxford who co-authored the report.

Greenpeace published an interactive map as a companion to the study, showing how little ocean life is currently protected compared with the wide swaths of ocean that could be protected with its proposed network of protected areas.

This is big: Our report shows we can protect a THIRD of our global oceans over the next decade

- Tackle climate change

- Give wildlife a safe place

- Protect precious ecosystems

- Keep our oceans safe from human exploitation

Oceans cover 70 percent of the planet’s living space and include 89 million square miles which are completely unprotected because they lie outside of national borders—currently, just two percent of the world’s oceans are protected. Greenpeace’s plan to establish conservation zones in 30 to 50 percent of the oceans would help ocean ecosystems recover from decades of worsening plastic pollution, overfishing, fossil fuel drilling, and acidification brought on by increased carbon in the world’s atmosphere.

“The speed at which the high seas have been depleted of some of their most spectacular and iconic wildlife has taken the world by surprise,” said Callum Roberts, a marine conservation biologist at the University of York. “Extraordinary losses of seabirds, turtles, sharks, and marine mammals reveal a broken governance system that governments at the United Nations must urgently fix. This report shows how protected areas could be rolled out across international waters to create a net of protection that will help save species from extinction and help them survive in our fast-changing world.”

The study took into account the socio-economic impact the sanctuaries would have on global fishing industries, showing that “networks representative of biodiversity can be built with limited economic impact.”

As delegations gathered in New York to discuss a treaty aimed at protecting oceans, Greenpeace urged world leaders to consider the groundbreaking “30×30” study as a guide for how to ensure a healthy future for marine life as well as the entire planet.

“The negotiations taking place here at the UN are crucial because, if they get it right, governments around the world could secure a Global Ocean Treaty by 2020 which has the teeth to realize a network of ocean sanctuaries, off-limits from harmful human activities,” said Dr. Sandra Schoettner of Greenpeace. “This would give wildlife and habitats space not only to recover, but to flourish. Our oceans are in crisis, but all we need is the political will to protect them before it’s too late.”

To help the plan a team of academics has released a detailed plan of how we could link up a global chain of vast marine reserves across previously unprotected international waters.

As the UN debates the details of a plan to start regulating the High Seas – the two-thirds of the world’s oceans which are in international waters – scientists are presenting a range of options on how to protect these crucial ecosystems.

‘The policy opportunity this represents is much rarer than once in a lifetime,’ says marine ecologist Douglas McCauley of the University of California, Santa Barbara. The question is ‘how we should protect two-thirds of the world’s oceans, [and] it’s the first time in human history that this has ever been asked.’

Currently, less than five per cent of our oceans have any protection and that falls mostly in territorial waters. Campaigners such as Sylvia Earle have been calling on the UN to step in and control the exploitation of at least a third of the world’s oceans – it had previously agreed that 10 per cent should be protected by 2020. Some of the analysis suggests at least 50 per cent needs to be protected.

The UK is supporting the bid to extend the protection and this week’s meeting is a key step in formulating plans that take advantage of recent research analysing a growing torrent of data from satellites, tagged animals and survey ships about the state of our open oceans.

Environment Secretary, Michael Gove, welcomed a report which is the result of a year-long collaboration between academics at York and Oxford universities and the environmental group Greenpeace.

‘From climate change to overfishing, the world’s oceans are facing an unprecedented set of challenges,’ said Gove. ‘It is now more important than ever to take action and ensure our seas are healthy, abundant and resilient. I join Greenpeace in calling for the UK and other countries to work together towards a UN High Seas Treaty that would pave the way to protect at least 30 per cent of the world’s ocean by 2030.’

Experts say that in addition to a wealth of marine life and complex ecosystems, the high seas play a key role in regulating the earth’s climate, driving the ocean’s biological pump that captures huge amounts of carbon at the surface and stores it in the oceans’ depths. Without this process, they warn the atmosphere would contain 50 per cent more carbon dioxide and become too hot to support human life.

The reportbreaks the world’s oceans into 25,000 squares of 100x100km and then maps 458 different conservation features including wildlife, habitats and key oceanographic features. It also models hundreds of scenarios for how a planet-wide network of ocean sanctuaries would function.

They combined data using software that can draw maps to maximise benefits while minimising costs. The team also added constraints, such as requiring the model not to place the most productive fishing grounds within a reserve and to favour networks of larger, connected reserves over smaller, isolated patches. Out of hundreds of possible configurations for the 30 per cent and 50 per cent scenarios, they picked what they thought offered the best protection for biodiversity with the fewest trade-offs.

Prof Roberts warned that to protect 30 per cent of the most valuable conservation features you may have to cover as much as 50 per cent of the world’s oceans because of the way habitats and species are distributed.

A second team, which includes Douglas McCauley and is funded by Pew Charitable Trusts in Philadelphia, US, is taking a similar approach, but its scenarios envision 10 per cent and 30 per cent coverage. It plans to present its maps at the next round of treaty negotiations in August.

A third team, funded by the National Geographic Society is dividing the entire world’s ocean into blocks 50 kilometres and ranking them by conservation value. The team hopes to unveil its work early next year at the final UN treaty negotiations.

However, the treaty will face stiff opposition particularly from countries with large high seas fishing fleets. And even if negotiators can agree on large-scale protection, they will still face plenty of difficult issues. For example, should reserves bar all exploitation, or allow some fishing or mining, perhaps only during certain seasons? How should the rules be enforced? And how and by whom would this be policed.

As Sylvia Earle said: ‘Once we stop killing all the tuna, the swordfish, the sharks, the grouper and all the other fish on an industrial scale, there is a chance that the pattern of appalling destruction I have seen in my life can become a time of recovery.’

Article adapted from Dive and Common Dreams

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.