Conservationists Denounce Netflix Documentary as Misleading and Unhelpful

To say that there has been some controversy over the recent Netflix production Seaspiracy would be like suggesting the ocean is a little moist.

Billed as an investigative documentary into a global conspiracy of organisations that downplays, ignores or even supports the negative impacts that the fishing industry has on the world’s oceans, the film by director and presenter Ali Tabrizi has received a great deal of criticism, both positive and negative.

Seaspiracy has received a great deal of praise on social media, with many commenters suggesting they have been motivated to become vegans as a result of watching the movie – no doubt welcomed by Tabrizi and Seaspiracy’s producer Kip Andersen, both of whom are vegan activists.

But there has been an immense amount of negative criticism from the scientific community, especially those that represent the marine conservation organisations that have spent decades trying to improve the world’s oceans – and which Tabrizi has effectively maligned as being part of an international conspiracy to benefit the fishing industry.

The problems are compounded by – as many scientists have pointed out – by the film-maker’s continual use of factually inaccurate, or misleading data. One of the examples most often referred to is the claim that the world’s oceans will be devoid of fish by 2048 – a number that was a sidenote in a 2006 academic paper modelling the decline of global fish stocks, and which was debunked by its own author in a follow-up paper in 2009.

There is much to applaud in Seaspiracy, as Tabrizi highlights the slaughter of dolphins at Taiji and the Faroe Islands, the failure of some countries, Japan in particular, to abide by the moratorium on whaling, the appalling practice of shark-finning, terrible problems associated with bycatch and the serious violations of human rights on fishing boats – including slavery.

He also devotes a significant amount of time to the plastic pollution that is ravaging our oceans, and legitimately questions why the world is focussing on banning plastic straws to save the ocean which, he says – in probably the best line of the whole film – is ‘like banning toothpicks to save the Amazon’.

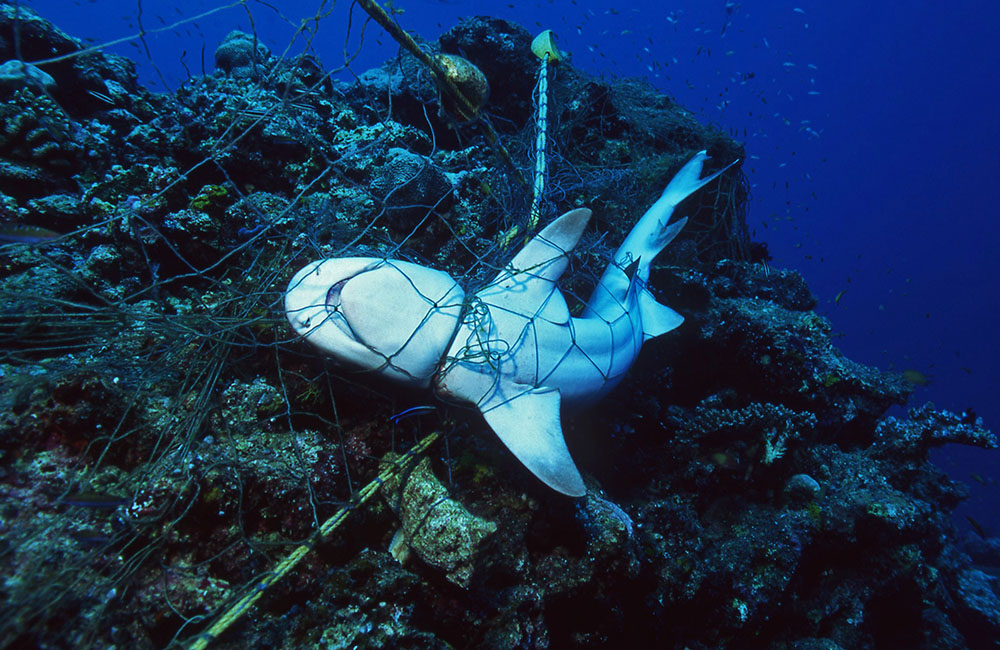

It is right that he discusses the very serious problem of abandoned, lost and discarded ‘ghost’ fishing gear, but he makes a misleading claim that the majority of ocean plastic comes from the fishing industry. According to a 2019 Greenpeace report, while fishing gear forms the largest percentage of large plastic in the ocean, it contributes just 10 per cent to the total. That’s 10 per cent too much, of course, but 80 per cent of the ocean’s plastic comes from the land – the bottles and bags that divers see on an almost daily basis – so blaming the bulk of oceanic plastic pollution on the fishing industry is not only misleading, but shifts attention away from the real source of the problem.

All of the problems discussed in Seaspiracy are real, and exposing them is to be welcomed, but once sensationalism, exaggeration and demonstrably false claims are made, just like the fable of the boy who cried wolf, many people will stop believing that the actual facts presented are factual.

On the other side of that coin is the problem that, when presented with what appears to be an informed piece of investigative journalism, many people will believe exactly what is presented, and this is where the major disappointment of Seaspiracy (other than its name, for which Conspirasea would surely have been a better choice!) is promulgated.

By demonising conservation networks that are working to reduce the impacts of the fishing industry as part of a global conspiracy working on behalf of the fishing industry, Seaspiracy risks creating a backlash against the very organisations that are fighting to protect the world’s oceans.

Dismissing sustainable fishing as impossible and labelling sustainable certification by the Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) – the regulatory body which oversees the management of fisheries – as ‘not credible’, Tabrizi ignores the scientific evidence that rigorously managed fisheries have an immensely positive impact on fish populations. The MSC has issued a response to the accusations levelled against it by Seaspiracy’s producers, as have some of the other participants who feel that their views have been misrepresented or taken out of context.

Included in the list of respondents is Mark Palmer, associate US director of the International Marine Mammal Project (IMMP), the organisation behind the US version of the ‘Dolphin Safe Tuna’ label. While Palmer is quoted in the movie as saying that the ‘Dolphin Safe’ label does not completely guarantee that no dolphins are killed, Tabrizi claims that the labelling is, therefore, ‘a complete fabrication’, while ignoring that its use has reduced dolphin mortality among US fisheries by some 95 per cent – from more than 130,000 animals in the 1980s to 819 documented deaths in 2018. Palmer writes in his statement that he ‘provided [Seaspiracy’s] crew with extensive information on how the Dolphin Safe label is used for the protection of dolphins, [but] none of this footage was used in the documentary.’

The Plastic Pollution Coalition, which the producers claim has deliberately ignored the fishing industry’s contribution to plastic pollution, released a statement saying that the film-makers ‘bullied our staff and cherry-picked seconds of our comments to support their own narrative. Despite our efforts to provide documentation of the plastic pollution crisis and our work before, during, and after, they chose instead to grossly distort and mischaracterize our staff and organization. ‘

Later in the statement, the PPC also write that, as a result of Seaspiracy‘s misrepresentation of its organisation, its staff have received hate mail, death threats and been ‘doxxed’ on social media.

There is no denying that the fishing industry has many very serious questions to answer. Unfortunately, although Seaspiracy brings these questions to a massive global audience, it offers no solutions to any of the problems – apart, that is, from switching the world’s population to a plant-based diet.

Given that the film-makers are vegan campaigners with a past portfolio of vegan-activism films (Tabrizi’s previous film Vegan (2018), and Andersen’s Cowspiracy (2014) and What the Health (2017)), this is unsurprising, but it ignores the complex relationship of humans with the world’s oceans, and it is, much as campaigners might want to argue otherwise, not a plausible solution.

According to WWF, approximately 3 billion people around the world rely on fish as their primary source of protein – and, in many parts of the world, as their sole source of income. Turning to a vegan diet might be easy if you live in a country where alternatives to meat are reliably available, but for several billion people around the world, it simply is not an option. It is also the case that many people who do have the choice are just not going to make it.

Seaspiracy also ignores other complex questions such as, for example, the problem of invasive lionfish in the Caribbean. Removing them from reefs in the tropical Atlantic has become an environmental necessity to prevent the catastrophic decline of coral reefs and other species in the region, and selling the lionfish for food makes it an attractive financial proposition for local fishers to do so.

Seaspiracy claims that nobody was talking about any of these problems before – which is not true; none of the issues raised in the movie are new, but, thanks to the power and popularity of Netflix, these issues to the forefront of the global conversation about conservation, and that is something to be celebrated.

But if it means that marine conservation organisations are smeared by unfounded conspiracy theories, with the scientists who work for them receiving death threats as a result of Seapiracy‘s misrepresentation, then this needs to be addressed.

There is undoubtedly much that is rotten about the global fishing industry, but there are many good people out there who have dedicated their lives to repairing the damage we’ve done to the world’s oceans, with positively measured success.

Let’s hope we can refine the conversation that Seaspiracy has brought to the table, and make sure it doesn’t undo the decades of work that has been done to redress the balance we need to create for a sustainable partnership with the marine environment.

Reproduced from: http://divemagazine.co.uk/eco/9329-seaspiracy-how-not-to-save-the-ocean