We Know Plastic Is Harming Marine Life. What About Us?

Read this story and more in the June 2018 issue of National Geographic magazine.

In a laboratory at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, in Palisades, New York, Debra Lee Magadini positions a slide under a microscope and flicks on an ultraviolet light. Scrutinizing the liquefied digestive tract of a shrimp she bought at a fish market, she makes a tsk-ing sound. After examining every millimeter of the slide, she blurts, “This shrimp is fiber city!” Inside its gut, seven squiggles of plastic, dyed with Nile red stain, fluoresce.

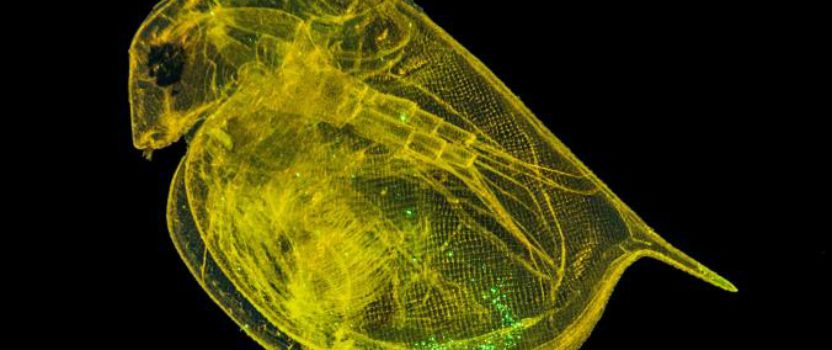

All over the world, researchers like Magadini are staring through microscopes at tiny pieces of plastic—fibers, fragments, or microbeads—that have made their way into marine and freshwater species, both wild caught and farmed. Scientists have found microplastics in 114 aquatic species, and more than half of those end up on our dinner plates. Now they are trying to determine what that means for human health.

So far science lacks evidence that microplastics—pieces smaller than one-fifth of an inch—are affecting fish at the population level. Our food supply doesn’t seem to be under threat—at least as far as we know. But enough research has been done now to show that the fish and shellfish we enjoy are suffering from the omnipresence of this plastic. Every year five million to 14 million tons flow into our oceans from coastal areas. Sunlight, wind, waves, and heat break down that material into smaller bits that look—to plankton, bivalves, fish, and even whales—a lot like food.

Fish caught by children who live next to a hatchery on Manila Bay in the Philippines live in an ecosystem polluted by household waste, plastics, and other trash. PHOTOGRAPH BY RANDY OLSON

Experiments show that microplastics damage aquatic creatures, as well as turtles and birds: They block digestive tracts, diminish the urge to eat, and alter feeding behavior, all of which reduce growth and reproductive output. Their stomachs stuffed with plastic, some species starve and die.

In addition to mechanical effects, microplastics have chemical impacts, because free-floating pollutants that wash off the land and into our seas—such as polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and heavy metals—tend to adhere to their surfaces.

Chelsea Rochman, a professor of ecology at the University of Toronto, soaked ground-up polyethylene, which is used to make some types of plastic bags, in San Diego Bay for three months. She then offered this contaminated plastic, along with a laboratory diet, to Japanese medakas, small fish commonly used for research, for two months. The fish that had ingested the treated plastic suffered more liver damage than those that had consumed virgin plastic. (Fish with compromised livers are less able to metabolize drugs, pesticides, and other pollutants.) Another experiment demonstrated that oysters exposed to tiny pieces of polystyrene—the stuff of take-out food containers—produce fewer eggs and less motile sperm.

The list of freshwater and marine organisms that are harmed by plastics stretches to hundreds of species.

It’s difficult to parse whether microplastics affect us as individual consumers of seafood, because we’re steeped in this material—from the air we breathe to both the tap and bottled water we drink, the food we eat, and the clothing we wear. Moreover, plastic isn’t one thing. It comes in many forms and contains a wide range of additives—pigments, ultraviolet stabilizers, water repellents, flame retardants, stiffeners such as bisphenol A (BPA), and softeners called phthalates—that can leach into their surroundings.

Some of these chemicals are considered endocrine disruptors—chemicals that interfere with normal hormone function, even contributing to weight gain. Flame retardants may interfere with brain development in fetuses and children; other compounds that cling to plastics can cause cancer or birth defects. A basic tenet of toxicology holds that the dose makes the poison, but many of these chemicals—BPA and its close relatives, for example—appear to impair lab animals at levels some governments consider safe for humans.

Studying the impacts of marine microplastics on human health is challenging because people can’t be asked to eat plastics for experiments, because plastics and their additives act differently depending on physical and chemical contexts, and because their characteristics may change as creatures along the food chain consume, metabolize, or excrete them. We know virtually nothing about how food processing or cooking affects the toxicity of plastics in aquatic organisms or what level of contamination might hurt us.

The good news is that most microplastics studied by scientists seem to remain in the guts of fish and do not move into muscle tissue, which is what we eat. The United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, in a thick report on this subject, concludes that people likely consume only negligible amounts of microplastics—even those who eat a lot of mussels and oysters, which are eaten whole. The agency reminds us, also, that eating fish is good for us: It reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease, and fish contain high levels of nutrients uncommon in other foods.

That said, scientists remain concerned about the human-health impacts of marine plastics because, again, they are ubiquitous and they eventually will degrade and fragment into nanoplastics, which measure less than 100 billionths of a meter—in other words, they are invisible. Alarmingly these tiny plastics can penetrate cells and move into tissues and organs. But because researchers lack analytical methods to identify nanoplastics in food, they don’t have any data on their occurrence or absorption by humans.

And so the work continues. “We know that there are effects from plastics on animals at nearly all levels of biological organization,” Rochman says. “We know enough to act to reduce plastic pollution from entering the oceans, lakes, and rivers.” Nations can enact bans on certain types of plastic, focusing on those that are the most abundant and problematic. Chemical engineers can formulate polymers that biodegrade. Consumers can eschew single-use plastics. And industry and government can invest in infrastructure to capture and recycle these materials before they reach the water.

In a dusty basement a short distance from the lab where Magadini works, metal shelves hold jars containing roughly 10,000 preserved mummichogs and banded killifish, trapped over seven years in nearby marshes. Examining each fish for the presence of microplastics is a daunting task, but Magadini and her colleagues are keen to see how levels of exposure have changed over time. Others will painstakingly untangle how microbeads, fibers, and fragments affect these forage fish, the larger fish that consume them, and—ultimately—us.

“I think we’ll know the answers in five to 10 years’ time,” Magadini says.

By then at least another 25 million tons of plastic will have flowed into our seas.

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.