Just a Few Pieces of Plastic Can Kill Sea Turtles

All over the world, sea turtles are swallowing bits of plastic floating in the ocean, mistaking them for tasty jellyfish, or just unable to avoid the debris that surrounds them.

Now, a new study out of Australia is trying to catalog the damage.

While some sea turtles have been found to have swallowed hundreds of bits of plastic, just 14 pieces significantly increases their risk of death, according to the study, published Thursday in Scientific Reports.

Young sea turtles are most vulnerable, the study found, because they drift with currents where the floating debris also accumulate, and because they are less choosy than adults about what they will eat.

Worldwide, more than half of all sea turtles from all seven species have eaten plastic debris, estimated Britta Denise Hardesty, the paper’s senior author and a principal research scientist with the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization in Tasmania. “It doesn’t matter where you are, you will find plastic,” she said.

Six of the seven species of sea turtles are considered threatened, although many populations are recovering.

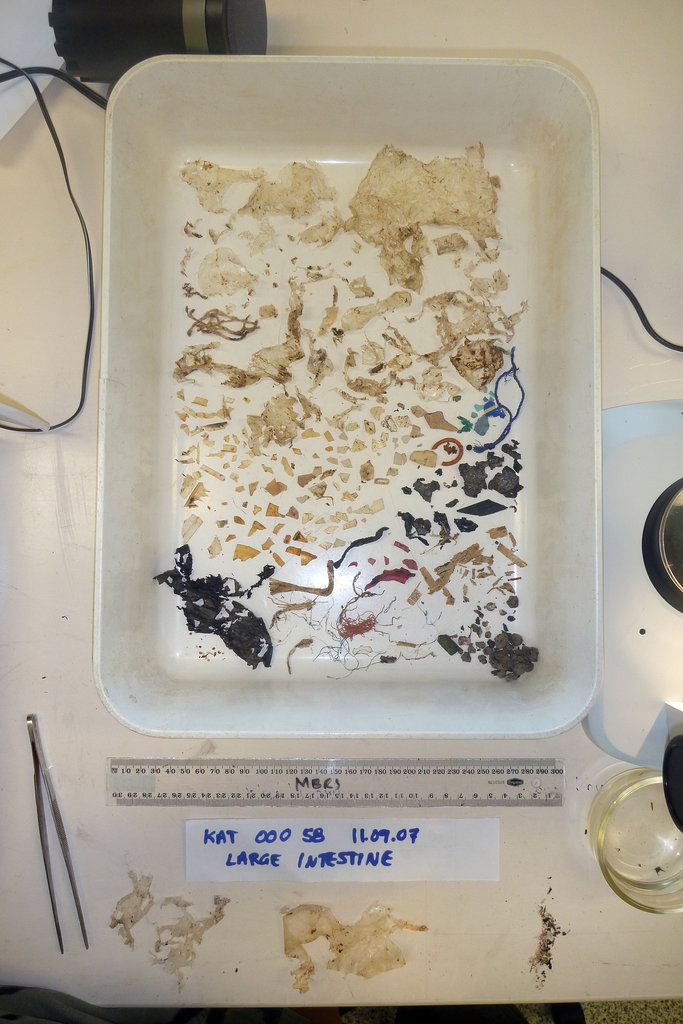

The study examined data from two sets of Australian sea turtles: necropsies of 246 animals and 706 records from a national strandings database. Both showed animals that died for reasons unrelated to eating plastic had less plastic in their guts than those that died of unknown causes or direct ingestion. But the deaths are hard to pin down. “Just because a turtle has a plastic in it, you can’t say that it died from it, except in very extenuating circumstances,” Dr. Hardesty said. Even a single piece of plastic can occasionally cause death. In one case a turtle was found with its digestive tract blocked by a soft piece of plastic; in another, its intestine was perforated by a sharp piece of plastic.

Plastics removed from the intestine of a sea turtle. The study found that half of juvenile turtles would be expected to die if they ingested 17 plastic items. Photo Credit: Kathy Townsend

In others, a variety of plastic material was found inside their digestive tracts — as many as 329 pieces in one sea turtle. Because of their anatomy, sea turtles cannot vomit up something once they’ve swallowed it, Dr. Hardesty said, meaning it either passes through their gut or gets stuck.

For a juvenile of typical size, half the animals would be expected to die if they ingested 17 plastic items, the study concluded. Sea turtles can live to be 80 or more years old, Dr. Hardesty said, with juveniles too young to reproduce ranging up to age 20 to 30.

The study’s innovation was to try to determine this inflection point, where the load of plastic becomes lethal, said T. Todd Jones, a supervisory research biologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Hawaii.

“There’s always been this question of when is plastic too much?” Dr. Jones said.

An animal that swallows a lot of plastic might appear healthy, Dr. Jones said, but might be weakened by plastic in its gut limiting food absorption.

Mark Hamann, a turtle expert and associate professor at James Cook University in Townsville, Australia, said he hoped that studies like this one would provide a sense of the scope of the problem. In some areas with high levels of plastic pollution, like the Mediterranean and the southern Atlantic Ocean, turtles are unable to avoid the debris, while in other areas it is less of a problem.

“We know individual turtles are dying, but we don’t know yet whether enough turtles are dying to cause population decline, and that’s where we’re heading to now,” Dr. Hamann said.

Jennifer Lynch, a research biologist with the National Institute of Standards and Technology in Hawaii, took issue with the way the study measured vulnerability to plastic.

In her own research, she has seen animals that aren’t harmed after swallowing 300 pieces of plastic, so she doesn’t believe that 14 pieces pose such a high risk of death. “They ate a lot of plastic but it did them no harm,” Dr. Lynch said of the animals she’s examined. “They swallow it and they poop it out.”

The difference between the two studies, Dr. Lynch said, was the health of the animals. “There’s a very strong bias in their study toward very sick, dead animals,” she said. “We looked only at live, healthy animals that died because they drowned on a fishhook.”

Dr. Lynch said the new study should have focused on the weight of the plastic rather than the number of pieces. A single piece could range from a speck of microplastic to an entire snack bag, she noted.

“It’s just that this magic number of 14 pieces I think is too low,” Dr. Lynch said. “I think we have a lot more to do before we know what concentration of plastic causes physiological and anatomical impacts.”

Dr. Lynch does agree that sea turtles are eating too much plastic. “We have to get this pollutant under control if we don’t want to kill half of our sea turtles.”

The vast majority of plastic off Hawaii, she said, comes from the international fishing industry, which is prohibited from dumping its old fishing lines and crates overboard, but often does it anyway — and faces no consequences. “Teeth is what’s needed,” Dr. Lynch said.

Dr. Hardesty said she thinks it’s possible to reduce the turtles’ exposure to plastic with a variety of approaches, from incentives to bans for high-impact, frequently littered items.

“The stuff that ends up in the ocean was in somebody’s hand at some point in time,” she said.

Reproduced from the New York Time, Sept 13, 2018: By Karen Weintraub

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.