Keeping Shark Encounters Safe and Enjoyable

On 7 December 2018, the Red Sea’s Brothers Islands were closed to divers for the rest of the year, after four biting incidents from oceanic whitetip sharks, one of which resulted in serious injury to a diver. The action has been taken to allow the sharks to return to their natural

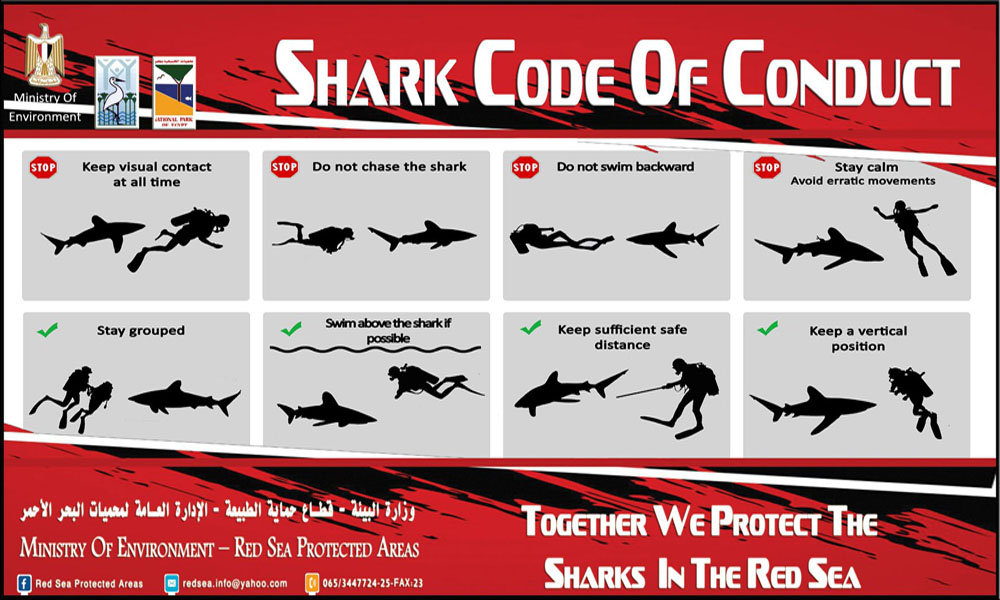

Much speculation has been made as to the reasons behind the bites at the Brothers, including diver pressure, illegal fishing, and both the deliberate and accidental feeding of the sharks. Some people have also suggested that the bites (including the most serious) are the result of divers not knowing how to properly interact with sharks, nor how to react if a shark suddenly becomes aggressive. In light of this, here are some safety tips on how to interact properly with sharks that are classed as ‘potentially dangerous’.

Do Not Panic

First and foremost is not to panic. Sharks are incredibly attuned to chemical imbalance, electrical impulse and sound. This is how they hunt in the open ocean, and what makes them able to sense even a small drop of blood or an injured fish from miles away. Panic raises a diver’s heart-rate, body temperature and adrenaline levels, all of which could trigger a response from the shark. Flailing arms and legs heighten those physiological responses, which may further provoke the animal.

Know the Signs

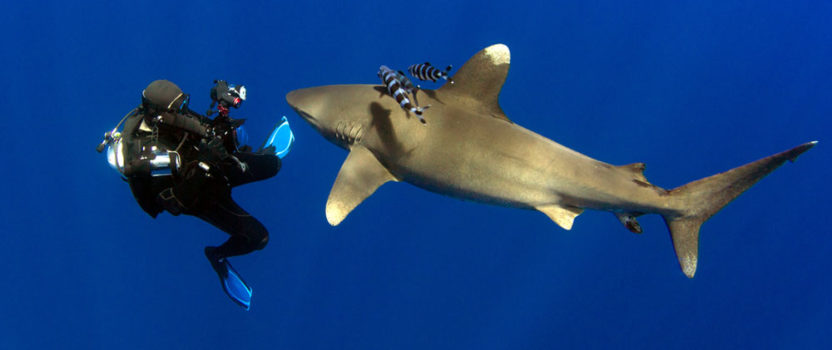

Sharks swimming in a calm and relaxed manner do not, in general, pose a threat. This is their default, energy conserving state. Oceanic whitetips are particularly well known for circulating through groups of divers, making close approaches to each diver in turn. It’s partly what makes them so popular. Any change in that behaviour, however, may signal that the shark has become agitated, and more caution must be applied. Look out for sudden, jerky movements, rapid movement of the tail and bursts of speed. Sharks sometimes display an aggressive warning posture: arched back, emphatic side-to-side movement of the head and tail, with their pectoral fins held almost vertically in the water, instead of their normal horizontal aspect.

Remain Vertical in the Water

Perfect horizontal trim might be the optimum standard for scuba diving buoyancy control, but not when dealing with aggressive sharks. Most large predators are wary creatures – think of all the times you’ve seen a nature documentary where predators target young or wounded animals – there is much less risk that the predator itself will be injured. Remaining upright gives you a much more dominant profile in the water, and not what the shark is expecting, causing it to remain wary and hesitant of getting too close.

Keep Your Eyes on the Shark

Sharks are masters of the art of stealth. If you lose sight of a shark, it can turn up unexpectedly and close by. It’s been suggested that you should not make continuous eye-contact as that might be seen as a challenge. Nevertheless, keep track of the animal until it loses interest and swims away. It’s worth waiting and observing for a few minutes more to check if it returns.

Keep Your Distance

Do not attempt to move closer to the shark, chase after it, or under any circumstances attempt to reach out and touch it. Let it approach under its own terms, and if you feel uncomfortable, move slowly to the side and out of its path.

Move Cautiously, Don’t Swim Away at Speed

Rapid movements and swimming away backwards as fast as possible may be interpreted by the shark as signs of weakness. This is what prey does – it panics and flees. Once the shark starts to think that it has established dominance over its intended target, it may lose its wary caution. Never turn your back on a shark and attempt to swim away quickly. This is natural prey behaviour, you will never outswim it, and it leaves your legs vulnerable.

Stay Close To The Reef

If you’re close to a coral reef, back up slowly against the reef wall, or sink to the bottom and crouch down among the coral if possible (try to find a sandy patch, of course), all the while keeping your eyes on the shark. By doing so, you remove the range of approaches available to the shark, and pose less of a threat to its natural domain. If the reef stretches to the surface, you can begin to slowly ascend to more comfortable depths if necessary.

Group Together

Get as close as you possibly can to your buddy, especially if you are off the reef and in the blue. This way you present a larger and more dominant appearance to the shark. Hovering back-to-back is ideal so that you can maintain a 360-degree perspective while the shark is circulating – especially if there is more than one animal in the vicinity. The more divers in the pack, the better, but stay as a tightly knit group until the shark leaves the area.

Avoid the Surface

It is a commonly held belief that sharks are more likely to target swimmers, snorkellers and surfers than divers. There is some evidence that this is the case, but it should not be taken as read that sharks will never target divers. Nevertheless, at the surface, you are no longer on an ‘equal’ footing with the shark, you have a more limited range of movement, and are therefore more vulnerable. If you absolutely have to surface, do it as close to the boat or reef as possible, and preferably as a group. Keep your face in the water and maintain a lookout if the shark is still in the area.

Above or Below?

Some advice – including that from the Egyptian Ministry of the Environment, above – suggests maintaining a position above the shark. Some divers disagree and say to stay below. It’s difficult to find a reason why either should be the case, and is likely dependent on the species of shark, or whether you’re diving close to the reef or out in the blue. It’s also worth pointing out that there is no reason a shark would maintain a constant depth, and could be above or below you with a flash of its tail if it wanted to be. In my personal opinion, if I’m underwater and away from the reef, then I’d rather maintain a position above the shark. By doing so and remaining upright in the water, I can see my whole body, my fins are the first things in the shark’s line of sight, and it would be easier to swim closer to the reef, boat or a buddy while keeping an eye on the shark if it was underneath me. Although surface time should be minimised under normal circumstances, in the unlikely event of a real emergency, I’d also rather be able to surface for help than be forced to stay underwater. Local guides will likely have better advice given the area and the type of shark in question, so make sure you ask during the briefing.

If All Else Fails…

While extraordinarily rare, every now and then, sharks attack. In the extremely unlikely event that a shark takes hold of you, the best advice is to fight back. This is, however, a last resort, and should never be used against a shark that simply gets too close or ‘bumps’ a diver, which are quite natural behaviours. If, and only if, the shark persists in pushing an attack, or has taken hold of you, striking the eyes and the gills, where sharks are particularly sensitive, may cause it to flee. Some suggest striking the snout, where sharks are also sensitive, but which is is also closer to their teeth. Shouting through your regulator may help, and there is some anecdotal evidence that pushing back – that is finning towards the shark, rather than trying to back away – may cause the shark to think again. Once again: this is an extremely rare situation, and should never, ever be used against a shark without justification.

The Internet is full of debates over how humans should interact with sharks, and various culls after fatal incidents prove only that some people believe that humans should have dominion over the ocean realm. We don’t – the ocean belongs to them, and everything else in it, and we should be cautious and respectful every time we enter the water where sharks are known to be present.

Remember that hundreds of thousands of people get in the water every day, and there are only a tiny number of shark-related incidents around the world every year, of which only a handful have proven fatal.

Still, as many as 100 million sharks are slaughtered every year as a result of bycatch and for their fins, and almost every extant species is currently under threat of existence.

Divers have done an immense amount to rehabilitate the image of sharks over the years, and by following better scuba diving practices, we will be able to continue to do so.

http://divemagazine.co.uk – By Mark ‘Crowley’ Russell

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.