Levels of plastic pollution in Monterey Bay rival those in Great Pacific Garbage Patch

Plastic concentrations are as high as the Pacific Garbage Patch in Monterey Bay National Marine Sanctuary

Monterey Bay has a reputation as one of America’s most pristine ocean environments: It’s a national marine sanctuary and far away from heavy industry.

But a groundbreaking study published Thursday has found levels of plastic pollution in the water similar to those found in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. The pollution is made up of trillions of tiny bits of debris, roughly the size of a grain of rice or smaller, floating from near the surface to thousands of feet underwater. The particles are being consumed by small ocean animals, the study found.

“It’s incredibly sobering,” said Kyle Van Houtan, chief scientist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium.

“This is not a place you expect to find a lot of plastic, a lot of toxics,” he said. “What it shows is the pervasive effect of the human ability to transform the oceans into a nonnatural state, even in a place where we have a lot of protections.”

The study, a joint effort by the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI) and Monterey Bay Aquarium, is the first to document how plastic pollution in the ocean is widespread and exists not just at the surface but in deep waters as well. The report was published on June 6, 2019, in the journal Scientific Reports.

“Our findings buttress a growing body of scientific evidence pointing to the waters and animals of the deep sea, Earth’s largest habitat, as the biggest repository of small plastic debris,” said Anela Choy, lead author of the paper and an assistant professor of oceanography at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at UC San Diego.

Choy and other researchers used unmanned underwater robots to collect water samples near the shoreline at Moss Landing Harbor and roughly 15 miles out in the ocean and at depths of as much as 3,000 feet below the surface.

They found concentrations of plastic particles at roughly 2 particles per cubic meter near the surface and as high as 10 to 14 particles per cubic meter roughly 1,000 to 2,000 feet underwater.

By comparison, plastic pieces in the famous Great Pacific Garbage Patch farther west in the remote Pacific Ocean north of Hawaii have been found near the surface at about 10 particles per cubic meter.

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, an area where ocean currents come together to concentrate litter and other debris, is not a giant floating collection of large plastic objects. Rather, it is a concentration of tiny pieces of confetti-like plastic that have been broken down in the ocean over years.

The new study found that such plastic pollution appears to be everywhere in the world’s oceans.

The scientists said Thursday that many of the particles they sampled in Monterey Bay were heavily degraded and likely have been in the water for years or even decades. The debris probably has moved in and out with the ocean currents, Van Houtan said, from perhaps thousands of miles away.

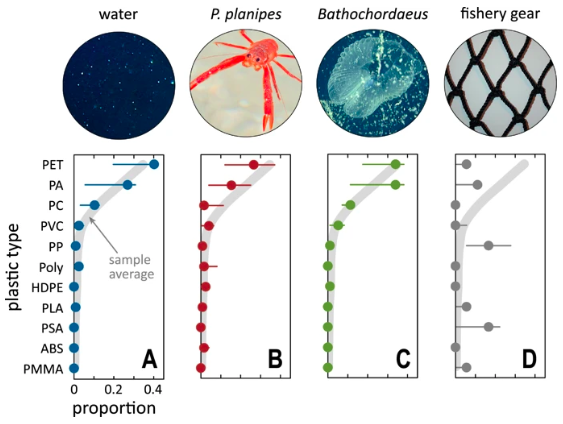

Roughly 40 percent of the particles detected in the study are PET (polyethylene terephthalate) plastic, found in common food and beverage containers and other household uses, he said.

“That’s something we can very easily control,” he said. “We simply don’t need to use these materials, and we can choose reusable items and not generate pollution that ultimately ends up in the ocean.”

Cleaning up pollution that stretches over thousands of miles of ocean and extends down thousands of feet deep is not practical, scientists note.

Van Houtan said researchers are still studying how long the plastic pieces take to break down and what their impacts are on wildlife. Large plastic debris, such as discarded fishing nets, can entangle and kill seabirds, sea lions, whales and other wildlife. Such debris also can be a choking hazard.

Less is known about the effects on wildlife of the tiny pieces of plastic outlined in Thursday’s study. The study found the debris being ingested by deep sea crabs and other small ocean animals.

The pollution might not kill them but can harm their health because the plastic takes up space in the animals’ digestive systems that otherwise would be available for food, Van Houtan said. Much more research is needed to understand the overall impacts to ocean health, he said.

“Animals with high plastic burdens have more limited growth than animals with lower plastic burdens,” Van Houtan said. “We are still trying to understand how these plastics are moving through food webs in the oceans.”

By PAUL ROGERS Bay Area News Group

Link to Original Article

Leave a Reply

Your email is safe with us.